Wirral minor and field names

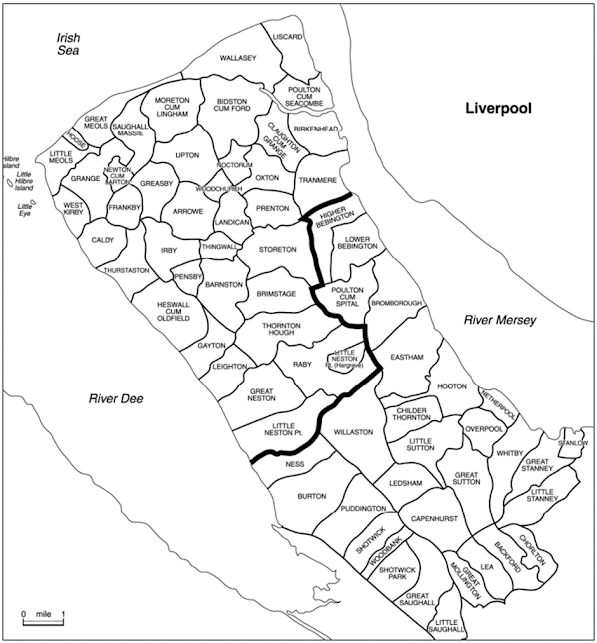

Wirral parish map (19th cent.). The bold line

demarks the approximate boundary of the 10th century Norse enclave,

based on baronial manor holdings and place names. Courtesy of Chester and

Cheshire Archives & Local Studies.

The Wirral

peninsula in north-west England was once home to a vibrant colony of

Scandinavian settlers, many of whom were Norsemen expelled from Ireland. The

arrival of one group was led by Ingimund in 902, but there were others,

including Danes. The intensity of the settlement is borne out by the

distribution of major or settlement names in Wirral, such as Arrowe, Caldy,

Claughton, Gayton, Larton, Lingham, Mollington Torold, Ness, Neston, Storeton,

Thingwall, Thurstaston, Tranmere, the -by names (Frankby, Greasby,

Helsby, Irby, Kirkby in Wallasey, Pensby, Raby, West Kirby, Whitby and the now

lost Haby, Hesby/Eskeby, Warmby, Kiln Walby, Stromby and Syllaby) and the

Norse-Irish Liscard and Noctorum. Some further settlement names, such as

Birkenhead, Heswall and Woodchurch, are of Anglian origin but were influenced

by the incoming Norsemen.

The

intensity of settlement can, however, perhaps best be gauged from the minor or

field names. Outstanding examples are brekka ‘slope, hillside’ (e.g. The

Breck, Flaybrick, Wimbricks and the Newton Breken), slakki ‘shallow

valley’ or ‘hollow’ (e.g. the Heswall Slack, the Bromborough Slack, Acre Slack

Wood and the West Kirby Slack, the many instances of ærgi ‘shieling, pastureland’ (e.g. Arrowe Park), þveit ‘clearing’ (e.g. the many thwaites in the Bidston area), klint ‘projecting

rock’ (e.g. the Clynsse stone (1642), now the Granny stone, at the

Wallasey Breck and the Clints at Brotherton Park, Bromborough), hestakeið ‘horse

race track’ (at Irby and Thornton Hough) and over 100 instances of the element rák ‘lane’.

The

Wirral carrs and holms

Of

particular interest are the 51 instances of kjarr (carr/ker) and

24 of holmr (e.g. Lingham) in north Wirral, names associated with marshy

land: kjarr is an Old Norse word meaning ‘brushwood; marsh; boggy land

overgrown with brushwood’ and holmr is Old Norse meaning ‘dry ground in a marsh;

island of useable land in a marshy area; a water meadow’. It is notable that

there are no instances in Wirral of the corresponding English names – elements such

as mersc ‘marsh’ and ēg ‘dry ground in a marsh’ – for the same features.

All names

were recorded in the 19th century tithe map apportionments or earlier.

Bidston: Bedestoncarre (1306; now

Bidston Moss), Wallacre, Oxholme, Olucar (1347), Holmegarth

Claughton: Near Holmes Wood, Further Holmes

Wood (1824)

Grange: Carr x2, Carr Farm, Carr Field

Great

Meols: Carr Side

Field, Carr Hall Farm, Carr Farm, Carr House, Carr Lane

Hoylake: Carr Lane

Landican: Carremedowe (1306) now Carr

Bridge Meadow, Carr Bridge Field, Near Carr Bridge Field

Leighton: Holme Hays

Little

Meols: Carr x2, Carr

Lane Field, Carr Field, Carr Side Hey, Carr Hey

Moreton

cum Lingham: Lingham,

Lingham Lane, Dangkers (now Danger) Lane, Bottom o’th’carrs, West Car, West

Carr Meadow, West Carr Hay, Holme Hay, Big Holme Hay, Little Holme Hay, Holme

Intake

Neston

(Great & Little):

Holme Heys

Newton

cum Larton: Newton

Car (1842), Sally Carr Lane (now footpath), Carr Lane, Carr, Carr Meadow,

Holmesides, Banakers

Overchurch

and Upton: Salacres#,

Salacre# Lane, Lanacre#, Hough Holmes, Le Kar (1294)

Oxton: Holm Lane, New Home (1831), Home

Field, Home Hey, Little Home, Carr Bridge Meadow, Carr Field Hey

Pensby: Carr House Croft

Prenton: Five Acre Holme, Bridge Holme, Top

Holme, Lower Holme, The Holme, Higher Holme

Saughall

Massie: Carr Farm,

Carr Houses, Carr Meadow, New Carr, Carr, Carr Hay, Old Carr Meadow, Old Carr

x2, Carr Lane

Wallasey: Wallacre Road/Waley-Carr, Routeholm

(1306)

Woodchurch: Lower Ackers#, Higher Ackers#

Great

Stanney: Holmlake

(1209)

Stanlow: Holmlache (1209)

# = last

element could be Old Norse kjarr or akr

Distribution map of field/track names in “carr” (filled circles) and “holm” (open circles)

Plotted on a map, they reveal an interesting trend and most congregate around the Rivers Birket and Fender. They suggest that much of north Wirral was of relatively low-quality farming land subject to flooding and tidal inundation, a feature that persisted through the centuries until the sea defences and embankments were constructed and completed in the late 19th/early 20th centuries.

Persistence

of a Scandinavian dialect

Studies by

scholars such as Kenneth Cameron (1997) have shown that the minor names in an

area tell us a great deal about the kind of vocabulary of the community. The

distribution of the carrs and holms taken alongside the

distribution of all minor names in Wirral with Scandinavian elements attest to

the persistence of dialect reflecting the intensity of the original settlement.

Distribution

map of field/track names containing Scandinavian elements. Square marks

Thingwall

Taken alone,

individual names describing a landscape feature are limited to the occurrence

of that feature – so that the distribution of carrs and holms shows

the concentration of boggy areas in Wirral as much as the Norse influence of

naming. The original Scandinavian words kjarr and holmr would

have been borrowed early into English as ker and holm, and the

evidence of the use of these elements in Wirral is all from after the Norman

Conquest, the earliest recorded examples being Holmlache (1209) in Stanlow

(perhaps the same place as Holmlake (1209) in Great Stanney, le Kar (1294)

in Overchurch and Routeholm (1306) in Wallasey, where holmr is

compounded with the Old Norse adjective rauðr ‘red’.

But perhaps the fact that the normal Old English words for these particular

topographical features are completely absent in these areas is of some

significance. The Norse-derived words had become the normal ones in Wirral when

the names were given.

Wirral was

not entirely boggy and uninviting. In Bidston, close to the Bedestoncarre and

Olucar, we have evidence of extensive clearing with large numbers of thwaite-names:

from the 19th century tithe apportionments (with earlier forms

recorded in 1644 or 1646) we find The Cornhill Thwaite, The Great Thwaite,

Marled Thwaite, Meadow Thwaite, Salt Thwaite, Spencer’s Thwaite, Tassey’s

Thwaite, Whinney’s Thwaite and the associated Thwaite Lane. Earlier we find Inderthwaite

and Utterthwaite (both 1522), the Thwaytes and Oldetwayt (both

1357). Around the centre of the Norse enclave, moreover, we still find, for

example, Youd’s and Bennet’s Arrowe, Brown’s Arrowe, Bithel’s Arrowe, Harrison’s

Arrowe, Widing’s Arrowe, Wharton’s Arrowe etc., as well as associated names

such as Arrowe Hill, Arrowe Bridge and Arrowe Brook, a tributary of the River

Birket. The persistence of this word of Celtic origin, adapted by Viking

settlers abroad is not only evidence of a continuing dialect but also of the

continuation of a type of farming used (and still used) by the Norwegians, i.e.

transhumance, whereby cattle and sheep are pastured away from the farmhouse

during summer months, saving the nearby pasture for winter fodder.

Conclusion

The

distribution of topographical minor names tells us as much about the

distribution of natural features as it does about the people who named them. In

the case of the Wirral carrs and holms, the high density in the

former Norse enclave tell us about the distribution of boggy ground before the

modern construction of the sea defences. It also reflects the persistence of

the Scandinavian dialect throughout the centuries, and the absence of the

corresponding English names for the same feature is testament to the dominance of

this dialect in the medieval period.

Acknowledgements

The help

and advice of Dr. Paul Cavill of the English Place Name Society is gratefully

appreciated, as is that of Howard Mortimer (Wirral Council), Peter France and

John Emmett (local archaeologists). The help and patience of Paul Newman, Derek

Joinson, Margaret Cole, Caroline Picco and John Hopkins of Chester and Cheshire

Archives & Local Studies is also very much appreciated.

This is

an abridged version of an article originally written by Steve Harding and

published in the Journal of the English Place-Name Society in 2007.

Harding, S.E. (2007). The Wirral Carrs and Holms. Journal of

the English Place-Name Society 39, 45–57.

https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/ncmh/documents/dna/JEPNS-Nov-Dec2007.pdf

More articles about Vikings can be read on Steve’s Wirral

and West Lancashire Viking page:

https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/ncmh/vikings/wirral-and-west-lancashire-viking-page.aspx

Further

details of Wirral place names (and more) can be found in Ingimund’s Saga –

Viking Wirral (Third Edition):

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Ingimunds-Saga-Viking-Stephen-Harding/dp/1908258306/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1VKVC9RN6DWAA&keywords=Ingimunds+Saga&qid=1645426500&sprefix=ingimunds+saga%2Caps%2C85&sr=8-1

Sue

Bishop and Steve Harding

Comments

Post a Comment